On why we haven’t created “A Game for Good Muslims”

Ezekiel: Dysfunction You Can Trust (?)

We have multiple cards based in the book of Ezekiel, including "Bread Freshly Baked with Human Dung (4:12)," "Turning Fine Gold and Silver Jewelry into Gilded Dildos (16:17)," and of course "Lusting After Lovers with Donkey Genitals and Horse Emission (23:20)" [We've gotten multiple emails asking for assurances that the latter was included in the game].

One of our Ezekiel cards garners more silence than laughter when played by some brave soul: "God-sanctioned Gang Rape. (Ezekiel chapter 23)"

Go read the chapter. Then take a walk. Hug a puppy. Kiss your children. Practice watercolors. And then come back. We'll be here to talk when you're done.

We are not equipped to psychoanalyze the prophet Ezekiel, certainly not in a more thoughtful manner than the countless biblical scholars and psychologists who have gone before. The metaphors, images, and symbols employed by this prophetic voice offend the senses of most readers to the point of utter confusion and revulsion. This has led to lay and learned speculation about Ezekiel's relationship with the significant female figures in his upbringing and later life, an absentee father figure (God notwithstanding), the use of hallucinogens, alien-abductions, and attributing to him various mental maladies, including manic-depression, an anti-social personality disorder, and/or pathological aggression towards women.

Any, one, or none of these may be the case, but what would it matter? As one author/speaker elegantly penned, "God Uses Cracked Pots:" We're all broken. It's through those fissures that the living water flows through us and waters a thirsty ground. Or something like that. Something a lot less violent, disturbing, and unbearable compared to the gore laced spectacles with which Ezekiel confronts the people of Israel.

Or is that the point?

Hebrew Bible/Old Testament scholar Dr. Leslie C. Allen presented a perspective on Ezekiel's personal dilemma that is haunting: "It took language this outrageous to break the spell of the Temple."

Imagine talking to a people so convinced of their moral and social superiority, despite acts of oppressive avarice against those in poverty; a people who believe they are immune to God's punishment because they are His favorite nation — He has placed His house, His Ark, His Law, in His city, among His people; a people you love and desire to rescue from their impending doom, but God has already told you that this is impossible, they will not listen to you: What do you do? How do you get through to them?

By any means necessary. Through offense. Scandal. Shock and awe. Anything to prevent a valley of dried bones.

Perhaps the words of Abraham J. Heschel on prophetic speech corresponds with Dr. Allen's thought: "[the prophet's] images must not shine, they must burn."

Perhaps a prophet's occupational hazard has a corresponding benefit compared to the pastor/priest:

The prophet often screams from outside the congregation: warning, chiding, loving, from afar. This is so unlike the pastor/priest embedded in the congregation — and the social cliques, and the church board, and hierarchical structures of review — who weekly worries about which words might give offense, what edification will not be received well. Illustrations must be pruned, and picked and ripened so very, very carefully.

The prophet's only concern is that the orchard is on fire.

Perhaps a little Ezekiel is still needed in the world.

But what do we know: we made this game and you probably think we're going to hell anyway.

A vagina or two (Judges 5:30) or Why We Love Biblical Irony

The Song of Deborah (Judges 5) is one of the oldest writings of the Bible. It records how YHWH, the Divine Warrior, fights through and alongside His appointed champions against the forces of the Canaanites.

The poem is divided into three sections, each focused on the actions of a woman: Deborah— the prophet/judges; Jael—the wife of Heber the Kenite; and the mother of Sisera, the Canaanite general whose forces are oppressing the children of Israel. By the end of the poem, Deborah has led YHWH’s forces to victory over their Canaanites foes, and Jael has hammered a tent peg into the fleeing head of Sisera. Sisera’s mother is left waiting, wondering where her son is.

Standing upon her palace parapet she asks her handmaidens where her boy is, why has he not returned home? She comforts herself by assuming that he is collecting war prizes for his men, and presents for her, his loving mother:

“Why is his chariot so long in coming? Why tarry the hoofbeats of his chariots? … Are they not finding and dividing the spoil?—A girl or two for every man; spoil of dyed stuffs for Sisera, spoil of dyed stuffs embroidered, two pieces of dyed work embroidered for my neck as spoil?” (Judges 5:28b-30, NRSV)

“A girl or two for every man.” A רַחַם (racham) or two for every man.

But רַחַם (racham ) doesn’t mean “girl” (or “damsel” as in other translations). Though it has a variety of meanings, in this context at best it means “womb” and at worst “vagina.” We say “at worst” not because there is anything wrong with vaginas, but because the modern equivalent could be saying “pussy.” Roll those around the tongue:

“A womb or two for every man.”

“A vagina or two for every man.”

“A pussy or two for every man.”

Some argue that this is an example of metonymy, where a part represents the whole— like how one would say “The White House” or “Parliament” to represent the totality of government, or “wheels” to refer to a car; However, even if this were the case, the context is clear: Sisera’s mother is comforting herself with the hope that her son is bringing back not women, but objects of sexual conquest and gratification.

Beyond the fact that this portrays a male author of the text (we are doubting a woman would comfort herself with thoughts of female sexual subjugation at the hands of her bouncing baby boy, and every member of his army taking whichever two women they could find), it also portrays the Bible’s sense of irony.

By the time his mother says these words at the end of the poem, we know Sisera is not bringing back a vagina or two to rape and torture, and then possibly leave dead when he grows bored with them, this after killing their men and children.

No.

By the time his mother says these words at the end of the poem, we know Sisera lies dead because two women— not “wombs,” not “vaginas”— rose up against him, killed his men and their children, and then drove a phallus-like tent peg through his head.

Perhaps God has a sense of humor and more highly attuned sense of feminism than some give credit for, and inspires biblical writers with same.

But what do we know: we made this game and you probably think we’re going to hell.

"Ethnic Cleansing in the Name of The LORD" (The Book of Joshua) & "Not Giving a Shit About the Canaanites" (Most of the Old Testament)

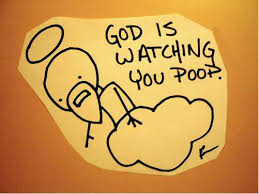

Special shit digging tools (Deuteronomy 23:12-13)

Thus saith the LORD:

You shall have a designated area outside the camp to which you shall go. With your utensils you shall have a trowel; when you relieve yourself outside, you shall dig a hole with it and then cover up your excrement. (Deuteronomy 23:12-13, New Revised Standard Version)

More than a picture of Hebrew sanitation practices on the battlefield, this passage provides a stunning insight into the mind of the Hebrew warrior, the crux of which is contained in the following verse:

Because the LORD your God travels along with your camp, to save you and to hand over your enemies to you, therefore your camp must be holy, so that he may not see anything indecent among you and turn away from you. (Deuteronomy 23:14, NRSV)

Simplified: Thus saith the Lord: “I don’t want to step in your shit.” No, really. Literally and metaphorically, God doesn’t want to step in our shit.

God was the head of the Hebrew army and no REMF. Throughout the Hebrew Bible the Divine Warrior rose from His southern stronghold to lead His people into battle: consider Exodus 15 , Deuteronomy 33 , Judges 5 , Psalm 68, and Habakkuk 3. This is why the people were admonished so often to not fear in battle: when they were told that YHWH will be with them, upholding them with a victorious right hand, that the enemy will cease to exist, that those who dare wage war against them will no longer be found on the earth (Isaiah 41:10-13 ), it was because God, literally, was on the battlefield kicking butts and taking names.

Now picture the average commanding officer striding through a war camp, inspecting the troops, and stepping a dusty open-toed sandal into a freshly minted, still steaming, lentil bean and corn strewn turd. That’s not going to end well for anyone. Not at all. And that was a mere mortal descending into defecation. Imagine it being God. But of course this verse is about more than avoiding the angelic scraping of scared sandals. As with most things in Deuteronomy this is about holiness. And as always, context is important.

Chapter 23 of Deuteronomy begins discussing people who were excluded from the holy assembly for ritual and cultic impurity: vs. 1 those with crushed testicles and severed penises [yes we have a card for this]; vs 2 certain types of bastards and their descendants; vs 3-8 addresses the Ammonite, Moabite, and Edomites because screw those Canaanites (however, you might also consider this perspective on that and/or this one as well.

From here the text moves to talk about waging war, describing how soldiers should act prior to battle: When you are encamped against your enemies you shall guard against any impropriety (vs 9). After covering what to do when a solider has had a wet dream (vs 10, and yes this is a card too), the fecal matter of the armed forces is next, because there is clearly a concern for what happens below the bellybutton, both front and back. The common link throughout these situations is holiness: in the socio-political assembly, in the Temple, and in the war camp, there are ways that the sacredness of the location is established and maintained. The rest of the chapter delineates social holiness: how to treat runaway slaves with grace and hospitality; rules against the exploitation of the daughters and sons of Israel as Temple prostitutes; prohibitions against loan sharking and usury within the community; and of course, fulfilling the vow to the Lord your God (vs 15-23). In other words, in all the places one would encounter God, holiness is expected.

Returning to our passage we see the potential arrival of God into the war camp: The Divine walking among the people, just like in Eden before the first couple stepped in a huge pile of their own making. This is significant. In the words of the renowned scholar the Gerhard Von Rad:

Israel knew that in these it was standing especially close and unprotected in Yahweh's field of operation. Therefore everything that was displeasing to Yahweh must be eliminated with more than usual care, that is to say, the camp must be ‘holy’. (Deuteronomy, 1966)

The Hebrews had an understanding of God walking in their midst.

Perhaps we should likewise take this mindset to heart.

Perhaps it’s not crazy to live life with the image of God walking beside us, through our days, decisions, and even defecations.

Perhaps we would be more careful to live lives of holiness in light of God having to watch where He steps.

But what do we know: we made this game and you probably think we’re going to Hell.

A Doxology (Jude 1:24-25)

We present this Canon Card with limited comment or commercial interruption:

Him who is able to keep you from falling and to make you stand without blemish in the presence of His glory with rejoicing; the only God our Savior, through Jesus Christ our Lord, worthy of glory, majesty, power, and authority, before all time and now and forever.

[And all the people said]

Amen.

An “amen” which reveals an ugly truth:

How we love being forgiven, but don’t love holiness.

Forgive our lack of trademark humor and sarcasm.

And besides what do we know: we made this game and you probably think we’re going to Hell.

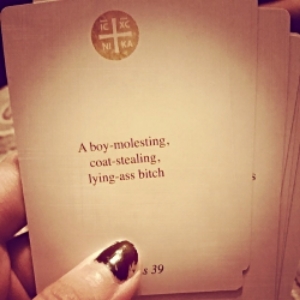

Boy-molesting, Coat-stealing, Lying-ass Bitch (Genesis 39)

This card is about Potiphar’s Wife and her treatment of young Joseph in Genesis chapter 39. But let’s call a spade a spade; you (or someone you love) is currently hung up on the fact that we used the word “bitch” in this game. We’ve heard the complaints.

For the record, we don’t like that word. It is an ugly, offensive word. We changed this card multiple times while creating this game. We talked of cutting this card out of the game altogether. The Bible has enough accusations of propping up the patriarchy and unrelenting misogyny without our help. We discussed it, seriously, for quite some time, until late one night we came to unflinching decision, and said in near unison, “no, she was a bitch.”

So now we have to defend that.

As an insult the word “bitch” supposedly has its roots in a comparison between a female dog in heat and a promiscuous or sexually aggressive woman. Some of the more modern usages describes a female (or male) who goes out of her way to harm, disparage, or interfere with the life of another, especially if that other person does not deserve the pain (for an insightful article on this topic, click here).

Are there other usages to this word? Yes. Do we condemn the word on those grounds, in those instances? Yes. But by the definitions above, in the biblical situation, Potiphar’s wife was ontologically a “bitch” regardless of how one would finesse the story.

This card isn’t “slut shaming” or supporting “rape culture,” it’s the exact opposite. Look at the facts:

A married woman, in a position of power (racially, culturally, financially, socially), sexually harassed her slave— Joseph— for months, maybe years. After he kindly declined her advances, she physically assaulted him in order to force a sexual encounter. And after Joseph literally ran out of the room, leaving her clutching the clothes she ripped off his fleeing body, she falsely accused him of attempting to rape her. As a result he was thrown into prison when his only crime was saying, “you’re married, this is wrong. Thank you, but no thank you” or at the very least, “I’m just not that into you.”

That, by definition, is a bitch move.

Despite all of this, Potiphar’s wife stands as an example of an evil that extends beyond gender, to systems of power in general.

Perhaps the real question is how often are you like her, using your position of authority to oppress those beneath you? How often will you not take “no” for an answer in a way that harms others?

Perhaps those offended by the use of this word should be more offended by the answer to those questions in their own lives. Lord knows those beneath you are.

But what do we know: we made this game and you probably think we’re going to Hell.

Suckling Milk from Sarah’s Sagging 90 year old Breasts (Genesis 21) ~ Infertility in the Bible

Not Being Your Brother's Keeper (Genesis 4:9)

We’ve heard the story: Cain killed his brother Abel. But the massive amounts of details missing from the story have made for centuries of diverse interpretations. What’s missing you ask?

Answer the following:

- Why did Cain and Abel feel the need to present offerings to God in the first place?

- How did God communicate his level of pleasure with the offerings received?

- What exactly happened between Cain and Abel that led to the killing? [Note: The majority of English translations do no justice to the lacuna (the missing information) present in the Hebrew of 4:8. It alternately reads, Cain spoke to his brother Abel. [full stop] And when they were in the field . . .” andCain said to his brother Abel, ‘ . . .’[speech missing]. And when they were in the field …” Many translations have placed the words “let’s go into the field/wilderness” into Cain’s mouth, but this is not present in the Hebrew text. Compare translations].

- What happened to Abel’s body? [Note: The text never says Cain buried him. God’s words about Abel’s blood crying out from the ground {min-ha’adamah} could mean Cain buried him or left his body where he was slain.]

- Who did Cain think would kill him? His parents? [Note: That would suck for them.]

- (And a favorite of Sunday School teachers everywhere) Where did Cain’s wife come from?

But let’s put aside these questions and their various interpretations for a moment;

Let’s also put aside notions that this text is about the struggle between stable subsistence farmers and nomadic herdsman, as neither the text nor the Hebrew Bible as a whole seem to actually actively value one profession over the other;

Put aside preachers and commentators who often go too far in psychoanalyzing Cain’s character to determine the content of his offering;

And put aside trite homilies about caring for our biological and adopted family, as if we were unaware that this was a moral requirement on our lives.

Instead we would like to highlight the four saddest and often overlooked features of this story:

1. This all began with an act of worship

Before his younger brother tagged along with the best crops, won God’s affection, and was subsequently slain, Cain commenced an unsolicited act of worship. Nothing in the tale or recorded history of the time says that there was a concept of sacrificial offerings to God. While scholars may debate the writing of the text showing a later editor’s hand, it is worth noting that said editors were silent in regards to Cain’s motive for the act, suggesting that worship is engrained in the human soul, is part of being made in the image of God. The best of actions from the best of intentions can be warped into something evil. Including depression, hatred, and murder.

2. Adam and Eve are still alive.

Imagine being those parents. Your youngest child is dead at the hands of your oldest. You blame yourself. How you raised them. Where you raised them. This would never have happened in Eden.

You hear the parallel between your conversation with God and your boy’s. You also hear the questions asked, as if omniscience were not at play. But you also hear your boy’s reply, absent of the deference and shame you brought before your creator.

Like both your boys, you now understand death. And on that note . . .

3. Cain had no way of knowing Abel would die

Think about it: Adam and Eve were the first exposed to the concept of “death,” whose meaning is debated by everyone who has ever read this text. Was God speaking of physical death, spiritual death, or both when he gave them the warning in Eden?

In any event, as the narrative progresses no one had ever physically died before Cain killed Abel. Often we speak of this as the first murder: it is also the first death recorded in the Bible. How was Cain to know that his actions would lead to his brother ceasing to exist in the land of the living?

This is made more poignant by the text’s repetition of their relationship: seven times it repeats that Abel is Cain’s brother. A thought clawing through Cain’s mind as he stands over the life-less body whose shared blood is upon his hands. When God asks, “where is your brother?” Cain’s reply can be read another way:

I don’t know where he is. Am I the guard, the savior, of my brother’s life?

Cain honestly had no idea what he had done.

4. Cain thinks he must avoid God from now on

In Genesis 4:14 Cain makes a bad situation worse. Like his parents he acts on something God never said [Note: God never said they couldn’t touch the fruit].

Cain’s curse was two-fold: 1) the ground which received his brother’s blood from his hand was cursed to him, and 2) and he will be a restless wanderer on the earth. He travels to the a “land of Nod”— the land of “wandering”—, but he also flees the presences of the Lord: something God never asked for.

Unlike his parents, Cain was not kicked out of the area. The curse upon his father was made worse indeed, but Cain was not asked to leave God’s presence. And as God wrapped his parents in clothing, Cain fails to realize that his mark is one of protection. His curse, the restless wandering, did not mean he had to travel away from God forever. That was Cain’s choice.

Perhaps we do not do the work we have been given to do as parents, as siblings of all humanity.

Perhaps we make impulsive decisions we can’t take back, that have unimagined consequences beyond our immediate ability to process.

But we do not have to wander too far afield. May we not choose to stay away too long.

And we may be going to Hell for making this game, but we know that’s true.

![O Come, O Come Emmanuel (Isaiah 7:14) [An Advent Card Talk]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55a9a1e3e4b069b20edab1b0/1483161046976-X5VJE3CMP9T957O72EII/3d-wallpapers-light-dark-wallpaper-35822.jpg)

Perhaps we should remember the women in the room when Ezekiel first uttered these words. They had been forcibly marched from their homes. They had watched their families die. Some had been raped by the Babylonians. How did they feel? Perhaps we should remember the women who read these texts today, the women in our churches and homes, whose current situations are not too dissimilar to the women in exile by the rivers of Babylon. They have enough reasons to weep.