In response to the assertion, “God put that tree there because He just wanted humanity to fall!” STFU and RTFM.

“The Lord making your uterus drop and your womb discharge” AND “All the women saying, ‘Amen. Amen.’” (Numbers 5:22)

We have two Canon Cards based on Numbers 5:22, so this is a two for one deal. To be honest, we made the second card because the end of the verse reads like an animated gif from a hip hop video: And all the ladies in place said, “amen, amen!” All the ladies in the place: “amen!” And all the fella in the place . . .” But the context of the passage is far less friendly: what many have called “The ordeal of the bitter water.”

In Rabbinic study, Numbers 5:11-31 is known as the sotah law, based on the Hebrew word for “straying away” (satah) from the marriage covenant. This is also a well-known passage in “seriously, F$%$# the Bible and its oppression of women!” circles, both in and outside of faith communities and the interwebs.

In summary: A husband suspects his wife has been unfaithful, but he is unable to prove it (She may or may not be pregnant, and he doubts the child is his, but that is not directly indicated in the text). So the husband brings his wife to the priest with a special offering to settle the matter.

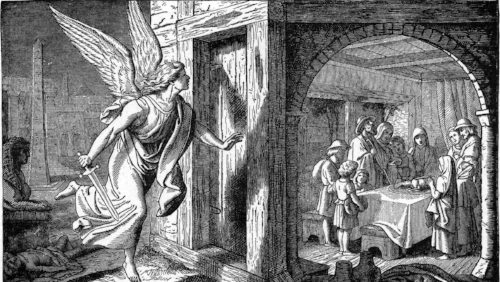

The priest takes the offering, makes a special potion, — “the bitter water”— has the woman “stand before the Lord” with her hair down, holding the offering, while he reads a curse/oath he has written on a scroll:

If no man has lain with you, if you have not turned aside to uncleanness while under your husband’s authority, be immune to this water of bitterness that brings the curse. But if you have gone astray while under your husband’s authority, if you have defiled yourself and some man other than your husband has had intercourse with you . . . the LORD make you an execration and an oath among your people, when the LORD makes your uterus drop, your womb discharge; now may this water that brings the curse enter your bowels and make your womb discharge, your uterus drop!”

To this the woman replies: “Amen. Amen.”

The priest then dips the curse/oath scroll into “the bitter water” and gives the potion to the woman to drink. The priest then takes the offering from her hands, waves it before the Lord, brings it to the altar, and everyone waits to see what will happen to the woman.

What does happen next, if she is guilty, is up for debate, for the water is bitter not (just) in taste, but in effect: what NRSV describes as “uterus drop and your womb discharge” has been alternately described as a miscarriage (if she was pregnant), the inability conceive ever again, and/or the internal malformation of her genitalia, among other horrible outcomes. Whatever the case, this is not a death sentence: the woman does not die. We emphasize this as we’ve heard so many speak incorrectly about this: nothing in the passage says the woman is being sentenced to death. But more importantly, we want to stress the fact that the woman is drinking the “bitter water” willingly.

[What?! How can you say that?! A paranoid husband who is probably off screwing every Mariam and Martha he can find is behind all this and an oppressive, patriarchal system is backing him up!! Even if she won’t die, there are things worse than death!]

Whoa! Take a deep breath and let’s return to the passage in context.

Theology in the Iron Age is partly magical/supernatural in how the world is viewed, especially compared to our (mostly) modern sensibilities, and comprehension of science and biology. There was a real belief among the people that if you swore an oath by God, and you were lying, God would strike you dead. If you did not fulfill your oath to God, God would strike you dead. If you open, touch, or smell the Ark of the Covenant, God will strike you dead. (Okay, maybe you’re safe smelling it, but by sheol, I wouldn’t be the one to risk it) Bottom line: if you partook of a sacred, cultic rite unworthily, God would strike you dead. Period. This holds true for this ceremony as well. Why is this important?

The woman who takes “bitter water” is swearing an oath before God. She is not undergoing a “trial by ordeal” as some suggest. This is not a rehashing of the Salem Witch trials. This is a ritual wherein God is the judge, jury, and executor of punishment, if punishment is needed. Notice the emphasis there. If.

This woman has not been found guilty of adultery, otherwise she would already be dead (c.f. Leviticus 20:10, Deuteronomy 22:22). The minimum of two witnesses has not been provided by the suspecting husband (Numbers 5:13), so at this stage the woman has options. The Talmud reminds that the woman does not have to partake in this ritual, she could even choose to leave the marriage if she wished (though she could not sue for alimony/further support). Yes, her standing in the community would be diminished, and we hear the cries about how she would not be able to survive as a single woman in that society: what other choice does she have? Fine. Keep reading.

In this passage, the woman chooses to take the oath, drink the potion, and says “amen” twice: “so let it be; so let it be. Or “bring it on!” Why, because she knows she’s innocent.

She knows that the mixture (as described) is completely harmless: Holy water, Tabernacle/Temple dirt, and any ink or residue from the scroll the curse was written on. [Some claim an herb or plant was added to the mixture, the alleged poison that will harm the women, but this is nowhere in the text] She knows that this potion will do nothing to her unless acted upon by a divine hand: that this is the only commandment in the Torah which requires God, not the community, for the penalty to take place. In other words, it is all on God to harm the women, not on her husband, or the oppressive patriarchy often read into this tale.

The woman drinks the water, says “amen, amen” with the swagger and confidence of a rap gawd, a spiritual/moral boss, because she knows she stands pure before God and no harm will come to her. That she will be protected from her accusing husband by the Hand of God.

One can argue that this is a warning for women against adultery, but conversely it is more of a warning for husbands: if God does not curse the woman, who is it that lied? Will the man now have the balls to call God a liar? Will the husband attempt to cast the first stone?

We wonder if the writer of John had this in mind when he penned the words about the (famous/infamous) “woman caught in adultery” (John 8:1-11)? In that story the ante has been raised as the woman was caught in the very act of adulatory, not just standing accused without proof by a jealous husband. Regardless, as with the case with the supposed sotah of Numbers 5, it is not in the hands of the community of men to decide what will become of her, men with sins all their own: no, it is in the hand of God.

Perhaps what we have here is not another example of systemic cultural violence against woman at the hands of an antiquated, patriarchal system, and instead is an example of protection of a woman falsely accused; a woman standing on the promises of fidelity made by a God who sees her as beautifully, fearfully, wonderfully, and equally made.

But what do we know: we made this game and you probably think we’re going to Hell.

“When your children ask, ‘what do these stones mean,’ you will tell them they represent ____.” OR Why “indoctrination” is not a four letter word

[Creed Card Talk]

Children have inquisitive minds. They ask “why” all the time because they want to learn, they want to understand. Adults assume the responsibility of being answer givers.

“ . . . Those twelve stones, which they had taken out of the Jordan, Joshua set up in Gilgal, saying to the Israelites, “When your children ask their parents in time to come, ‘What do these stones mean?’ then you shall let your children know, ‘Israel crossed over the Jordan here on dry ground.’ For the Lord your God dried up the waters of the Jordan for you until you crossed over, as the Lord your God did to the Red Sea, which he dried up for us until we crossed over, so that all the peoples of the earth may know that the hand of the Lord is mighty, and so that you may fear the Lord your God forever.” (Joshua 4:19b-24)

In the above example the people of Israel are memorializing God’s salvation and provision: bringing them out of the bondage of Egypt, through the Red (Reed) Sea, across the Jordan River. Though many trials would still to come, they had made it that far by the grace of God. And there was much rejoicing. They set up this monument as a physical, tangible, visible reminder of how what their shared experience shaped and defined their identity as a community, while serving as an educational tool for generations to come.

In order for a people, a community, a way of life to continue, for children to have their questions answered, there needs to be more than “religion education” [education about religion(s)]; instead “religious education” is needed. These are very different though the names are only separated by two letters.

RELIGION education is found in many public schools: the obligatory unit or course in “world religions” or “world mythologies” present in many progressive English/Language Arts and Social Studies curriculums. They are non-religious, non-sectarian, non- proselytizing lessons on what various people in various places believe and practice. You are not required to believe or practice those things in order to pass the class: just check the appropriate multiple-choice boxes and fill-in-the-correct-blanks to show that you can intelligently differentiate between The Five Fold Path, the Five Pillars of Islam, and the five books of The Torah without looking like an uncultured philistine at a dinner party, and so you can dominate while playing Jeopardy on an old school NES. There is no “indoctrination” of the students: there is no expectation or requirement for the students to receive the doctrine inside of themselves and accept them as true.

In RELIGIOUS education, members of a community are consciously and purposely “indoctrinating” those under them with the beliefs and practices which define that community. The student not only learns about the beliefs and practices, they are encouraged to actually believe them and authentically practice them: in order to be a part of the community, the student must believe and practice as the community does. (Think: “Sunday School,” “Hebrew School,” CCD, grandma’s not letting you go out to play on Sat morning until she’s imparted her spiritual wisdom for 45mins)

Some people view religious education as indoctrination, and indoctrination as a curse word, a pejorative: that indoctrinating children, or any people, is an oppressive system which robbing individuals of their freedom to think and make up their own minds. Some argue that all people should be given all the options and told to figure it out for themselves, especially children.

Putting aside the obvious issues (e.g. bastardized, non-religious, non- invested summarizes of religions in no way convey their true essence; how capable children are of “making up their own minds” about the existence of God, or picking a religion, with no guidance; etc.), there is nothing inherent in religious education which prevents “free thinking;” Furthermore, religious education, like all ideologies, is about preserving a heritage.

Religious education is the process by which a community says, “this is our shared identity within a community of belief and practice.” To say that this is “wrong” or “evil” is misguided. If a pastor, priest, rabbi, or imam indoctrinates her/his followers to consistently find ways to care for the people in their lives how stupid does the person sound who rails against such “evil indoctrination.”?

[How dare you fill those people’s heads with thoughts of caring for humanity?! Let them (somehow) decide for themselves without any oppressive input from themselves, and against their own (often) selfish and self-centered inclinations to only do good for those who benefit them! Stupid clergy on a power trip! ]

Yeah, shut that fount up.

Indoctrination is not the problem. The problem is never indoctrination. We need indoctrination to identify beliefs and practices of the groups we claim membership. The problem is what we indoctrinate others with: it is the content, not the capacity, which is the problem.

What are the meaning of the stones, the monuments you place in the life of those who come behind you? What are you indoctrinating your physical and spiritual children with? Biblical love and understanding or human intolerance and hate? Easy answers to tough questions or critical thinking which leads to tougher questions?

Perhaps we should spend less time complaining about how other people raise their children, or practice their beliefs, and spend more time examining the stone foundations we place our own children’s feet on.

But what do we know: we made this game, and you probably think we’re going to Hell.

Getting stoned for playing pick-up sticks on the Sabbath. (Numbers 15:32-36)

A bedtime story from childhood:

Once upon a time, the Children of Israel were in the wilderness (of course) and they found a man picking up sticks on the Sabbath. So they brought him before Moses, Aaron, and all the people, but they had no idea what to do with him. Then God said to Moses, “take him outside and bludgeon him to death with big freaking rocks!” So they did. Night night.

But there is more to the story than a mindless mob bent on following the bloodthirsty whims of a capricious deity. As always, let’s look at the context. Let’s start with the offense itself.

Picking up sticks? (Really God. U mad Son?) In His divine defense, God made it very clear that He would not abide work on the Sabbath. On Sinai He put it in the Ten Commandments, then added the death penalty, and then repeated it one more time for the cheap seats at the base of the mountain.He might have been serious. Hence the confusion of those who caught their Israelite brother picking up sticks on the Sabbath, in terms of what to do with him:

“Would you look at this idiot? It’s the Sabbath”

“I know, right?”

“Moron.”

“So.”

“So?”

“Do we kill him?

“He’s just picking up sticks!”

“Have you read anywhere in the Torah where it says ‘do no work on the Sabbath, except picking up sticks, ‘cause YHWH is completely cool with stick gathering despite His irrevocable law.’?”

“You know I can’t read.”

“Right. Me either. But we’ve heard what the Torah says.”

“Yeah.”

“Yeah.”

“You gonna cast the first stone?”

“Let’s just bring him to Moses.”

“Sounds like a plan.”

But let’s take a step backward.

The verses preceding the narrative are instructions for when an individual or the community has committed an unintentional sin. What you do when an “oops, I crapped my spiritual pants” moment arises, Numbers 15:22-29 clearly spells out what should be done to clean up the mess. (c.f. Leviticus chapter 4; 5:1-6:7; 6:24-30 & 7:1-10 ) Earlier in the book (chapter 5) instructions for intentional sins are given. (c.f. Leviticus chapter 1 & 6:8-13) In short, we aren’t perfect. We will screw up: intentionally and unintentionally. But we can make it right. The Torah has that all covered.

But this short narrative speaks of something different. This is not merely referring to intentional or unintentional sin. This deals with the person who has been confronted with their sin and raises a stiff middle finger to God and community.

The heart of the picker-upper of sticks is shown in two ways. First the narrative follows how sins can be forgiven (vs 22-29), as well as the death sentence for those who refuse to avail themselves of it, which is the legal preamble to the story:

But whoever acts high-handedly, whether a native or an alien, affronts the Lord, and shall be cut off from among the people. Because of having despised the word of the Lord and broken his commandment, such a person shall be utterly cut off and bear the guilt. (Numbers 15:30-31)

Second, it is confirmed by the Judge of his sentence: God orders the man’s death, not the people. God who knows the heart.This is a matter of repentance and remorse: whether or not the individual actually gives a good God’s damn or a damn about a good God.

No matter what you feel about the punishment itself, the sentiment is simple: there are things you do and do not do in community. You knew the rules. You knew the consequences. But you flagrantly broke them. And what’s worse, you don’t care that you did.

Actions have consequences. Sometimes dire ones.

Perhaps this is why after a Psalmist meditated on the effects of the Torah on his life— finding It more precious than gold and sweeter than honey from the honeycomb — he included the following request

Keep your servant also from willful sins;

may they not rule over me.

Then I will be blameless,

innocent of great transgression. (Psalm 19:13)

Perhaps we need to take stock of our actions and attitudes— providing less excuses and more accountability— because consequential reality can crush more completely than rocks.

But what do we know: we made this game and you probably think we’re going to Hell.

“Ruth’s sexy time with a drunken relative” (Ruth 3:4-10a) & “Not being a whore, but wearing one's uniform.” (Genesis 38:12-23)

[A two for one Card Talk]

I. Ruth

Sex sells. In some cases, sex also buys. At least that was Naomi’s thought in chapter 3 of Ruth. Apparently there are times when you have to pimp out your daughter-in-law to one of your relatives to survive.

Naomi had a plan, a sexy, sexy plan: To lockdown Boaz, Naomi told Ruth to wash, put on her nicest clothes, wait until Boaz was blackout drunk, “uncover his feet,” lay beside him, and allow Boaz to tell her what to do (3:1-5). Let’s address the text itself and see all the thinly veiled sexiness therein.

1. First, “feet” is a euphemism for genitals evident in other biblical passages (cf. Ex 4:25, Judges 3:24, 1 Sam 24:4, Isaiah 6:2 and Isaiah 7:20. We know some of those will hurt your head), and the image of “uncovering” someone is similarly linked to sexuality (cf. Gen 9, Lev 18, Deut 22:30 and 27:20). So at the very least, Naomi ordered Ruth to lift Boaz’s robes, leaving his naughty bits exposed, and then to allow him to take things from there. I wonder what Naomi thought a sleepy, drunk, half-naked man would tell the beautiful woman lying next to him to do in the middle of the night, especially if she’s the one who made him half-naked in the first place.

It is also noteworthy that the text indicates that time passes between Boaz’s uncovering and his awakening, leaving one to wonder what exactly woke him: a series of gentle caresses; a stiff, cold wind across the threshing-floor; a callous flick in the balls from a feminine hand tired of waiting for him to wake up?

2. In any event when he awoke, Ruth did not wait for his direction. Instead, she takes charge of the situation. After completing the majority of the steps, including “uncovering his feet” and lying beside him, when Boaz jerks awake, she tells him to spread his robe (and all that was under it) over her. Not only can one read the only sexual position approved by good fundamentalist Christians in foreign lands into this, but also the cleverness of Ruth using Boaz’s words against him.

In 2:12 Boaz tells Ruth that she would find a reward once covered by the wings/robe {kanaph} of YHWH. In 3:9 she uses the same word when ordering Boaz to action: “…spread therefore thy skirt {kanaph} over thine handmaid…”. In essence she said, “You said YHWH would cover me, how about you cover me, big boy?” Which is all the more poignant as Boaz, by law and social custom, had a legal obligation to do just that, but more on that below. For now notice how Ruth’s clever word play simultaneously allured and shamed him into doing what he was supposed to in the first place.

3. The location of this event is also telling. At least one prophet saw the threshing floor as a place of naughty behavior (cf. Hosea 9:1-2). Perhaps Hosea was thinking of Ruth and Boaz specifically.

4. And what about Boaz having her wait until morning to depart his side: what happened for the rest of the night? Did they talk about the barley harvest? Or the pitfalls of interracial marriages in the ancient Levant? Probably not. (We won’t say anything about Boaz sending her off with a skirt-full of grain, which a cynical person might see as a form of payment for services rendered.)

5. All of the above is suggestive enough, but the most compelling element is stated in Ruth 4:12, which contains these final words of blessing bestowed upon Boaz and Ruth by the elders of the city:

. . . and, through the children that the LORD will give you by this young woman, may your house be like the house of Perez, whom Tamar bore to Judah.

This comparison of Ruth to Tamar, which is often overlooked by our more prudish brethren, is the topic of the second Card Talk in this two for one.

II. Tamar

Genesis 38 tells the story of Tamar. In summary, Tamar was married to Judah’s first son Er who pissed God off in some unspecified way and was smote, smitted, got smotten . . . was killed by God. At this point, Tamar was in the same position as Ruth for Hebrew law and custom dictated that when a women is left widowed, she was to be “redeemed” by a kinsman of her dead husband —a go’el. Some male relative was to marry her. (cf. Deut 25:5-6) In Ruth’s case, that was an unnamed relative who turned down the opportunity, and then Boaz, who was next in line. For Tamar, that duty fell to her brother-in-law, Onan.

However Onan, just like the unnamed “redeemer” in Ruth chapter 4, did not want his children being the heirs to his dead relative instead of himself as the custom required— all land, wealth and notoriety gained for/by the children, would be attributed to the lineage of the dead. But, unlike the unnamed character in Ruth, Onan still wanted to get his freak on. So he had sex with Tamar, but then pulled out to “spill his seed in the dust.” Of course God killed him too. (Gen 38:9. Of course we have a Canon Card about this verse too.)

Judah had a third son named Shelah who should have married Tamar, but fearing that she was a bad luck charm for his boys, Judah told Tamar that Shelah was too young to marry, and sent her back to her father’s house, with promises that he (Judah) would give her notice when Shelah came of age.

Years pass and Tamar has not been contacted by Judah about marrying Shelah. Hearing that Judah is travelling on business, she disguises herself and sits at the entrance to a town on the way to Judah’s destination. It just so happens that Judah’s wife had recently died and he was horny. Seeing the disguised Tamar, Judah assumes she is a prostitute, and kicks his old-school, mack-daddy, Hebrew-vibe at her, saying, “let me come into you,” promising her a young goat as payment (Gen 38:16-17).

Tamar, being a very clever woman, pretends she required collateral until she gets the goat: She takes his seal, its cord, and the staff in his hand. He handed them over, gave her what he had, and then she left. Later Judah sent a friend with the goat and to get his swag back, but the friend couldn’t find her. When he asked the townspeople, “where is the prostitute?” they looked at him like he was crazy: they didn’t have any prostitutes. What kind of a village did he think this was? When Judah hears this, he decides to cut his losses and drop the matter lest people mock him for getting rolled by a woman who wasn’t even a professional prostitute.

About three months pass and Judah receives word through the rumor mill: “Your daughter-in-law Tamar has played the whore; moreover she is pregnant as a result of whoredom.” To which Judah says, “Bring her out, and let her be burned.” (Gen 38:24) But Tamar had planned for this:

As she was being brought out, she sent word to her father-in-law, “It was the owner of these who made me pregnant.” And she said, “Take note, please, whose these are, the signet and the cord and the staff.” Then Judah acknowledged them and said, “She is more in the right than I, since I did not give her to my son Shelah.” And he did not lie with her again. (vs. 25-26)

{Drop the Biblical mic}

Why does the writer of Ruth include a comparison between these two women from the mouth the religious/social leaders of the community? Because it gives a picture of all they shared and had to overcome.

a. Both are introduced as barren women with dead husbands

b. Both are at the mercy of a patriarchal system of being “redeemed” by a go’el

c. Both are initially denied the appropriate protection of that system by men who were concerned about the inheritance of their own children (Onan & unnamed man)

d. Both are further effected by the indifference of another male relative who could and should have stepped in sooner (Judah & Boaz)

e. Both used their intellectual prowess and sexuality to get that which they were already entitled.

There is no shame in Ruth or Tamar’s game. Nor should there be. They did what they had to do and were praised for it in the end. Doesn’t seem like God is condemning them, so why should we?

Perhaps, instead, we should focus on the selfish attitudes of the men in the stories who did not live up to their moral, social, and spiritual obligations.

Perhaps Good Christians (and the rest of the world) should spend some time addressing systems of oppression, especially systems were ostensibly constructed to protect our fellow persons, which are not working.

But what do we know: we made this game and you probably think we’re going to Hell.

On the Absence of "A Game for Good Muslims"

Ezekiel: Dysfunction You Can Trust (?)

We have multiple cards based in the book of Ezekiel, including "Bread Freshly Baked with Human Dung (4:12)," "Turning Fine Gold and Silver Jewelry into Gilded Dildos (16:17)," and of course "Lusting After Lovers with Donkey Genitals and Horse Emission (23:20)" [We've gotten multiple emails asking for assurances that the latter was included in the game].

One of our Ezekiel cards garners more silence than laughter when played by some brave soul: "God-sanctioned Gang Rape. (Ezekiel chapter 23)"

Go read the chapter. Then take a walk. Hug a puppy. Kiss your children. Practice watercolors. And then come back. We'll be here to talk when you're done.

We are not equipped to psychoanalyze the prophet Ezekiel, certainly not in a more thoughtful manner than the countless biblical scholars and psychologists who have gone before. The metaphors, images, and symbols employed by this prophetic voice offend the senses of most readers to the point of utter confusion and revulsion. This has led to lay and learned speculation about Ezekiel's relationship with the significant female figures in his upbringing and later life, an absentee father figure (God notwithstanding), the use of hallucinogens, alien-abductions, and attributing to him various mental maladies, including manic-depression, an anti-social personality disorder, and/or pathological aggression towards women.

Any, one, or none of these may be the case, but what would it matter? As one author/speaker elegantly penned, "God Uses Cracked Pots:" We're all broken. It's through those fissures that the living water flows through us and waters a thirsty ground. Or something like that. Something a lot less violent, disturbing, and unbearable compared to the gore laced spectacles with which Ezekiel confronts the people of Israel.

Or is that the point?

Hebrew Bible/Old Testament scholar Dr. Leslie C. Allen presented a perspective on Ezekiel's personal dilemma that is haunting: "It took language this outrageous to break the spell of the Temple."

Imagine talking to a people so convinced of their moral and social superiority, despite acts of oppressive avarice against those in poverty; a people who believe they are immune to God's punishment because they are His favorite nation — He has placed His house, His Ark, His Law, in His city, among His people; a people you love and desire to rescue from their impending doom, but God has already told you that this is impossible, they will not listen to you: What do you do? How do you get through to them?

By any means necessary. Through offense. Scandal. Shock and awe. Anything to prevent a valley of dried bones.

Perhaps the words of Abraham J. Heschel on prophetic speech corresponds with Dr. Allen's thought: "[the prophet's] images must not shine, they must burn."

Perhaps a prophet's occupational hazard has a corresponding benefit compared to the pastor/priest:

The prophet often screams from outside the congregation: warning, chiding, loving, from afar. This is so unlike the pastor/priest embedded in the congregation — and the social cliques, and the church board, and hierarchical structures of review — who weekly worries about which words might give offense, what edification will not be received well. Illustrations must be pruned, and picked and ripened so very, very carefully.

The prophet's only concern is that the orchard is on fire.

Perhaps a little Ezekiel is still needed in the world.

But what do we know: we made this game and you probably think we're going to hell anyway.

A vagina or two (Judges 5:30) or Why We Love Biblical Irony

The Song of Deborah (Judges 5) is one of the oldest writings of the Bible. It records how YHWH, the Divine Warrior, fights through and alongside His appointed champions against the forces of the Canaanites.

The poem is divided into three sections, each focused on the actions of a woman: Deborah— the prophet/judges; Jael—the wife of Heber the Kenite; and the mother of Sisera, the Canaanite general whose forces are oppressing the children of Israel. By the end of the poem, Deborah has led YHWH’s forces to victory over their Canaanites foes, and Jael has hammered a tent peg into the fleeing head of Sisera. Sisera’s mother is left waiting, wondering where her son is.

Standing upon her palace parapet she asks her handmaidens where her boy is, why has he not returned home? She comforts herself by assuming that he is collecting war prizes for his men, and presents for her, his loving mother:

“Why is his chariot so long in coming? Why tarry the hoofbeats of his chariots? … Are they not finding and dividing the spoil?—A girl or two for every man; spoil of dyed stuffs for Sisera, spoil of dyed stuffs embroidered, two pieces of dyed work embroidered for my neck as spoil?” (Judges 5:28b-30, NRSV)

“A girl or two for every man.” A רַחַם (racham) or two for every man.

But רַחַם (racham ) doesn’t mean “girl” (or “damsel” as in other translations). Though it has a variety of meanings, in this context at best it means “womb” and at worst “vagina.” We say “at worst” not because there is anything wrong with vaginas, but because the modern equivalent could be saying “pussy.” Roll those around the tongue:

“A womb or two for every man.”

“A vagina or two for every man.”

“A pussy or two for every man.”

Some argue that this is an example of metonymy, where a part represents the whole— like how one would say “The White House” or “Parliament” to represent the totality of government, or “wheels” to refer to a car; However, even if this were the case, the context is clear: Sisera’s mother is comforting herself with the hope that her son is bringing back not women, but objects of sexual conquest and gratification.

Beyond the fact that this portrays a male author of the text (we are doubting a woman would comfort herself with thoughts of female sexual subjugation at the hands of her bouncing baby boy, and every member of his army taking whichever two women they could find), it also portrays the Bible’s sense of irony.

By the time his mother says these words at the end of the poem, we know Sisera is not bringing back a vagina or two to rape and torture, and then possibly leave dead when he grows bored with them, this after killing their men and children.

No.

By the time his mother says these words at the end of the poem, we know Sisera lies dead because two women— not “wombs,” not “vaginas”— rose up against him, killed his men and their children, and then drove a phallus-like tent peg through his head.

Perhaps God has a sense of humor and more highly attuned sense of feminism than some give credit for, and inspires biblical writers with same.

But what do we know: we made this game and you probably think we’re going to hell.

"Ethnic Cleansing in the Name of The LORD" (The Book of Joshua) & "Not Giving a Shit About the Canaanites" (Most of the Old Testament)

Special shit digging tools (Deuteronomy 23:12-13)

Thus saith the LORD:

You shall have a designated area outside the camp to which you shall go. With your utensils you shall have a trowel; when you relieve yourself outside, you shall dig a hole with it and then cover up your excrement. (Deuteronomy 23:12-13, New Revised Standard Version)

More than a picture of Hebrew sanitation practices on the battlefield, this passage provides a stunning insight into the mind of the Hebrew warrior, the crux of which is contained in the following verse:

Because the LORD your God travels along with your camp, to save you and to hand over your enemies to you, therefore your camp must be holy, so that he may not see anything indecent among you and turn away from you. (Deuteronomy 23:14, NRSV)

Simplified: Thus saith the Lord: “I don’t want to step in your shit.” No, really. Literally and metaphorically, God doesn’t want to step in our shit.

God was the head of the Hebrew army and no REMF. Throughout the Hebrew Bible the Divine Warrior rose from His southern stronghold to lead His people into battle: consider Exodus 15 , Deuteronomy 33 , Judges 5 , Psalm 68, and Habakkuk 3. This is why the people were admonished so often to not fear in battle: when they were told that YHWH will be with them, upholding them with a victorious right hand, that the enemy will cease to exist, that those who dare wage war against them will no longer be found on the earth (Isaiah 41:10-13 ), it was because God, literally, was on the battlefield kicking butts and taking names.

Now picture the average commanding officer striding through a war camp, inspecting the troops, and stepping a dusty open-toed sandal into a freshly minted, still steaming, lentil bean and corn strewn turd. That’s not going to end well for anyone. Not at all. And that was a mere mortal descending into defecation. Imagine it being God. But of course this verse is about more than avoiding the angelic scraping of scared sandals. As with most things in Deuteronomy this is about holiness. And as always, context is important.

Chapter 23 of Deuteronomy begins discussing people who were excluded from the holy assembly for ritual and cultic impurity: vs. 1 those with crushed testicles and severed penises [yes we have a card for this]; vs 2 certain types of bastards and their descendants; vs 3-8 addresses the Ammonite, Moabite, and Edomites because screw those Canaanites (however, you might also consider this perspective on that and/or this one as well.

From here the text moves to talk about waging war, describing how soldiers should act prior to battle: When you are encamped against your enemies you shall guard against any impropriety (vs 9). After covering what to do when a solider has had a wet dream (vs 10, and yes this is a card too), the fecal matter of the armed forces is next, because there is clearly a concern for what happens below the bellybutton, both front and back. The common link throughout these situations is holiness: in the socio-political assembly, in the Temple, and in the war camp, there are ways that the sacredness of the location is established and maintained. The rest of the chapter delineates social holiness: how to treat runaway slaves with grace and hospitality; rules against the exploitation of the daughters and sons of Israel as Temple prostitutes; prohibitions against loan sharking and usury within the community; and of course, fulfilling the vow to the Lord your God (vs 15-23). In other words, in all the places one would encounter God, holiness is expected.

Returning to our passage we see the potential arrival of God into the war camp: The Divine walking among the people, just like in Eden before the first couple stepped in a huge pile of their own making. This is significant. In the words of the renowned scholar the Gerhard Von Rad:

Israel knew that in these it was standing especially close and unprotected in Yahweh's field of operation. Therefore everything that was displeasing to Yahweh must be eliminated with more than usual care, that is to say, the camp must be ‘holy’. (Deuteronomy, 1966)

The Hebrews had an understanding of God walking in their midst.

Perhaps we should likewise take this mindset to heart.

Perhaps it’s not crazy to live life with the image of God walking beside us, through our days, decisions, and even defecations.

Perhaps we would be more careful to live lives of holiness in light of God having to watch where He steps.

But what do we know: we made this game and you probably think we’re going to Hell.

![O Come, O Come Emmanuel (Isaiah 7:14) [An Advent Card Talk]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55a9a1e3e4b069b20edab1b0/1483161046976-X5VJE3CMP9T957O72EII/3d-wallpapers-light-dark-wallpaper-35822.jpg)

Perhaps we should remember the women in the room when Ezekiel first uttered these words. They had been forcibly marched from their homes. They had watched their families die. Some had been raped by the Babylonians. How did they feel? Perhaps we should remember the women who read these texts today, the women in our churches and homes, whose current situations are not too dissimilar to the women in exile by the rivers of Babylon. They have enough reasons to weep.