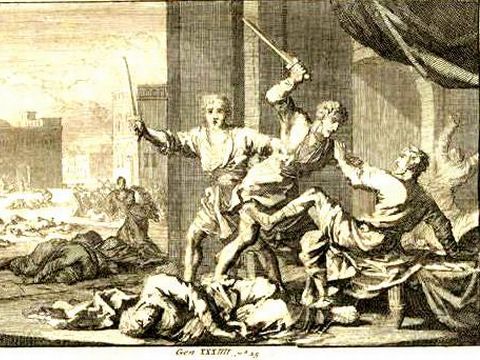

Being tricked into circumcision, and while still sore, having your throat slit, your sheep, oxen, asses, and everything in your house stolen, and your children and spouse enslaved, because you raped my little sister. (Genesis 34)

A Guest Card Talk by *Ryan Scott

My mom loved Little House on the Prairie. Well, she’s not dead, so I guess she still loves Little House on the Prairie, but when I was growing up, we watched it A LOT. I’ve probably seen every episode of that show (and there’s 205 of them) multiple times. I grew up to be a history major, so there was always an interest in the past – to see how people lived in a different time and place.

While I’m sure there’s some small measure of historical accuracy in that show, Michael Landon was not playing a character, he was playing Michael Landon, if he lived in late 19th century Wisconsin. The setting was in service of the story, not realism. A realistic depiction of frontier life and people would not have readily provided the family-friendly atmosphere the producers were going for.

That’s the rub. History was different. As much as present-day culture develops our own problems and bad habits, society is on a progressive trajectory overall. Things were different in 1872 – and it’s not just Half-Pint being upset her mom can’t vote or that she has to wear a dress to go fishing. There were real differences that, all things being accurate, would really turn off modern viewers.

Multiply that by a million when we go back 4,000 years to the life of Dinah. She’s the raped sister in question on the card. She was raped by Shechem, who then fell in love with her. His dad, Hamor, goes to Jacob (Dinah’s father) to essentially buy her as Shechem’s wife. Her brothers aren’t so keen on this and convince Hamor that his whole tribe will have to be circumcised to marry into the family. While they’re all recovering from the procedure, the brothers attack the village, kill all the men, and make off with everything (and everyone) else.

While we may be able to emotionally relate to some elements of this story, the world in which it takes place is utterly unrecognizable to us. We can’t bring really any assumptions into the narrative as we read. It’s a shock to the system.

Growing up going to church, I guess because I was a kid and incapable of deep analytical thought, I always put these stories in my own context. Guys like Noah, Joseph, and David were people, like my Dad or one of the neighbors – Michael Landons who just happened to live in the past.

There’s nothing wrong with that sort of understanding when you’re a kid. The problem is: many congregations never provide help for their parishioners to learn and develop a deep understanding of the stories they heard as kids. We keep that same mindset, along with the requisite shock and horror. (Not to mention the fact that Joseph and David are separated by several centuries – their lives, societies, and cultures would’ve been as foreign to each other as they are to us. Most of us, me included, really lack a historical perspective on the scriptures.)

This passage begins with Dinah leaving the house to visit the “women of the land.” Some Hebrew scholars call that a euphemism to say she’s going looking for the very thing she got. I’d call call this misogynistic jab a distraction, but it is significant in that women didn’t generally go roaming on their own. What we might read a nonchalant description of the freedom women enjoy in modern society, it’s more likely a warning that something bad will happen (as it always does when women have some measure of self-determination).

You also notice that Shechem rapes Dinah and then falls in love with her (evidently marrying the first person you sleep with has a longer and more sordid history than we ever suspected). It’s this odd juxtaposition that leads some scholars to assume this is really two accounts, both a rape and a courtship that have been thrown together. There’s some logic behind that – to later Israelites, intermarriage with the natives was a big no-no, and having Jacob consent to it would’ve been problematic – apparently even more problematic than mass murder. Go figure.

Hamor goes to Jacob, and offers to pay whatever bride price might be named so his son can marry the girl he raped. This is surely shocking to the modern reader, but if it were controversial at the time, it would have been because Hamor was so nice. As the ruler of the area, he probably didn’t have to make this whole situation work out – evidently he saw something in Jacob and his family that seemed worthwhile to partner with.

In fact, if you look at Deuteronomy 22:28-29, the Law of God’s people clearly outlines what to do in this exact scenario:

If a man happens to meet a virgin who is not pledged to be married and rapes her and they are discovered, he shall pay her father fifty shekels of silver. He must marry the young woman, for he has violated her. He can never divorce her as long as he lives.

Now the law came much later, so Jacob and his sons were clearly not aware that Hamor was only doing what God, in retrospect, would have wanted him to do. Instead they pull what’s known as the old “Snip, snip, stab,” routine on these guys, repaying the good faith it requires to take a crudely sharpened stone knife to your own penis with murder and theft. You’ll also notice it says they “carried off all their women.” Shechem raped a girl, then offered to marry her and provide for her comfort the rest of her life; the proper response to this, beyond the murder and theft, was to take all the women of the village and, presumably, rape them and keep them as slaves for the rest of their lives. And we wonder why “an eye for an eye” ended up being good news when that law finally came around?

In the end, Jacob regrets all these things his sons did, not for any moral compunction, but because it hurt his reputation with the rest of the people in the area (what with the lying and the trickery and all).

You can see the impossible cultural chasm between us and this story. If not, just trying picking a good guy. Is it the rapist? His father who tries to cover for him? Simeon and Levi, the lying, murderous, thieves? Jacob, who lets it all happen then callously complains about all the headaches his daughter’s rape has caused him?

I am an advocate of asking one thing from scripture when I read it: What does this say about God? That question helps us avoid making scripture into science or history or sociology in ways that it was never intended to be. But I’m not sure how you’d answer that question here either.

This might be the perfect passage to just thrown up our hands and surrender. We can go back through and explain why each party did what he did and why it fits with the cultural assumptions and morality of the time; and we can critique each action based on other parts of scripture and whatever theological progress has been made since, but what good would any of that do – besides wasting a bunch of time to conclude that rape is bad?

Ultimately, this passage and others equally perplexing, actually provide me with great comfort. The notion that scripture can’t be boiled down to some simple theology and that real, honest, grotesquely f’d up shit went down right in the middle of this larger story of redemption, helps remind me that faith and culture and morality are things we should struggle with. The world is not black and white. The very fact this game exists is, in some part, to provide a release valve for the things that don’t add up – a way of existing with faith in one hand and doubt in the other.

There are a lot of ways the story of Dinah can inform modern theology, especially from a feminist perspective, but in the context of the passage, she’s basically unimportant. At the time, women were property, nothing more; Jacob was more concerned with what a defiled daughter would mean for his own standing in society than any real concern for her well-being.

I know that intellectually. I went to seminary. I’ve studied. But there’s nothing that exists that could ever really make that make sense to my modern brain – even when similar things happen to real girls in our world today. There’s a distance there I can’t bridge.

At the same time, there’s also a testimony to redemption. As I said, this same story is one that eventually produces Jesus – and with him, the kind of morality that can finally mourn properly for Dinah and every other injured and unnamed woman, both past and present.

I still don’t know what this story says about God, but I do know what it says about the human condition: that the people of God (Jacob’s name gets changed to Israel in the very next chapter, for crying out loud!) can be just as cruel and uncaring and inhumane as anyone else.

That just seems really important for us to remember sometimes.

*[At the time of original posting] Ryan Scott lives with his wife, daughter, and two cats in Middletown, Delaware, where he is incredibly grateful for a unique, diverse group of neighbors and friends with whom he’s privileged to do life. He is an ordained elder in the Church of the Nazarene, a graduate of Eastern Nazarene College and Nazarene Theological Seminary, and the author of The Sinai Experiment. Ryan is also the national columnist for d3hoops.com; he loves watching sports, overanalyzing movies, and is attempting to stand on the highest point of every state. This post originally appeared on his blog at onemorethingblog.blogspot.com.

![Being tricked into circumcision, and while still sore, having your throat slit...because you raped my little sister (Genesis 34) [A Guest Card Talk]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55a9a1e3e4b069b20edab1b0/1467927097766-ZJCNQNC2VX0KSEV1NW86/NEWS1-257824122905732.jpg)